Our Blog

I am thrilled to be teaching “Design Methods & Research” this semester at California College of the Arts with Lucie Richter.

I am thrilled to be teaching “Design Methods & Research” this semester at California College of the Arts with Lucie Richter.

We are at midterm and have assigned the students a final project that should explore the core skills we expect them to learn:

Inspiration: develop skills to observe people in a way that inspire better design

Context: explore the full picture of where designs live

Design for use: propose solutions that fit appropriately into a system of use

Systems Thinking: understand multiple stakeholders and the effect of design choices

Empathy: develop a deeper understanding of others

Depth: seek to gain a new perspective on why people choose the products and services that they do

Ethics: respect and responsibility before, during and after observations

Synthesis: move beyond the obvious with new insights

Storytellingshare insights in a thoughtful and generative way

Helen Walters writes, once again, about how Design Thinking isn’t the magic bullet that some of us like to think it is, in a FastCo post. I found this paragraph helpful in articulating the value proposition of Participatory Innovation:

For designers to have strategic impact, they need to work with managers to ensure that the business elements of a project are being catered to, too. That might not play to the innate strengths of designers, but it’s vital for leaders to figure out ways for everyone to get along so that innovation can be a team sport. Otherwise, we’ll be left with bizarre stories such as the one that ran recently in The New York Times, with a Smart Design director arguing that the Flip camera was, in fact, just about perfect. Just not so perfect that Cisco didn’t decide to discontinue making the product. Executives don’t always make the right decisions, of course, and perhaps Cisco management did make the wrong call in this instance. But proclaiming that smartphones had no bearing on that discussion and arguing that all of the design decisions were correct smacks of hubris and myopia. Design doesn’t — shouldn’t — live in a bubble and designers need to bridge the divide between their world and business, not just lob ideas over the fence and hope for the best. As it stands, it takes a particular type of person who can span those two worlds. Those are the must-hire employees of the future.

Participatory Design acknowledges that we, as design researchers, are not seeking truth. What we gain from our interactions with participants is biased toward the questions we need to answer. The ideas that spark innovation and that are most inspiring to us as people who are intending to solve a problem—can come from many places.

With that in mind, Brendon Clark inspired me with the ways in which he has been exploring the boundaries of how much control he can give to others when he works with users and stakeholders in the field. Yesterday, in a chat with Brendon, a great influence of Participatory Design thinking for me, I realized myself how little control I give to those around me. He asked why.

“I… am trying to preserve the accuracy.”

Yet I have always acknowledged that the purpose of my approach is inspiration. When people ask me how I can stuffy only 6 people, I tell them that it only takes one clarifying story to change everything.

If I gave up some control to the designers and product managers in the field with me—to allow them to pursue the topics of the conversation that are most interesting—mightn’t we all be more inspired?

And the Participatory Design movement in Scandinavian, which I admire so much, has always been about bringing the user into the conversation as a equal participant. Easier heard than acted upon, apparently.

I see now how I tend to keep users in the dark during my field sessions—trying not to bias them by telling them what I want to know, or what I find most interesting. I remain neutral in the conversation– open and supportive– but still neutral, holding my card sort close to my chest, so to speak.

Brendon has been studying and writing about Performance as a way to put participants at the center of the conversation for innovation and design. He began his work, at the intersection of Anthropology and Participatory Design, with a focus on users and is now expanding his work to include stakeholders as participants as well. He says, “When you give people a stage, they naturally perform.” He sees our role as researchers as the people who create the stage.

Design’s relationship with Art has always been filled with tension. The respect has never felt entirely mutual. But the influence of Art on Design has informed more that the designer’s aesthetic sense, it reminds us to be accountable to the societal aspects of creating artifacts as well. Art has a longer history of influencing society, and Design can learn from that.

Design’s relationship with Art has always been filled with tension. The respect has never felt entirely mutual. But the influence of Art on Design has informed more that the designer’s aesthetic sense, it reminds us to be accountable to the societal aspects of creating artifacts as well. Art has a longer history of influencing society, and Design can learn from that.

Once you remove the artistic sensibilities of creating great work to offer into a cultural experience, the artifact one designs, or the experience on affords through a series of designs, the exercise becomes mechanical, technical.

HCI appears to have a stronger influence on the Interaction Designers in Silicon Valley these days than Design schools. Interaction Designers are more often expected to code, to move straight to software prototypes. Which shifts the focus of their education toward the mechanics of design, rather than the art and theory of design.

I worry when I see designers happy to execute on specs set by others, rather than asking questions about Who, When and Why. HCI, in making the process a technical task, makes the design process internal. HCI designers are armed with rules, structures and standards to apply to interactions. They don’t explore the context of use beyond the human factors, the inputs and outputs, the mechanics, because the right puzzle pieces are in their head to be figured out.

In the book, “Rehearsing the Future” by Halse, Brandt, Clark and Binder, the authors offer an excellent perspective on the similar evolution from user-centered design to participatory design (p. 13) in their manifesto:

The standard principles for what constitutes user-centered design are often not attuned to capturing the most influential aspects of the human experience. As designers are increasingly facing open assignments in complex social arenas where the definition of the problem is not given, but part of the challenge, new guidelines arise that the classical guidelines for good design do not address. […] The answer has less to do with the right order of information than with the socio-cultural situation in which it takes place.

It takes a flexible mind to gather a holistic understanding of complex contexts in order to find complete solutions to the systems problems that design problems look like today.

So many product research projects focus on influencing a decision, for which the researcher provides very specific insights about a specific portion of the overall problem.The beauty of Participatory Design projects is that the focus in not only on the initial task-at-hand that needs to be solved by the group, but also that the unstated goal becomes raising the knowledge of the people in the room.

When engaging in formative, strategic research for my product teams, and by engaging them throughout the process, my goal is to inform my stakeholders about a broader, more holistic context of use.

I hadn’t thought about this particularly, until a design director at work said to my director, “I want to work with you. But my people can’t focus on anything but research that helps them design what they are working on right now.” [Read into that “can’t” what you will] His meaning was that I can’t spend time sharing insights with the designers that don’t directly answer questions about this widget or that widget. Very disappointing. Especially when I’ve developed good relationships with the Product Managers, Marketing Managers and Engineers by sharing stories and insights about user experiences that helps to raise there OVERALL understanding of how people use communication tools.

My purpose for this kind of sharing of insights is mainly driven by my belief that I am not at MOST of the meetings where decisions are made– if they are even made in meetings. I also can’t research every little question that comes up, “Should this button go here or here?” “Do people share photos or quotes more often?” Therefore I need to arm the decision makers with an empathy and understanding of how different users make choices, so that EVERY decision they make is a bit more informed by real end-users.

I had the pleasure of attending the Participatory Innovation Conference (PINC) at the University of Southern Denmark on January 12, 2011. Dori Tunstall gave a remarkable closing keynote in which she performed a demonstration of three phases that design research/design anthropology/participatory design/user-centered design have evolved through in the past few decades. It was helpful to have her perspective on the key transitions:

I had the pleasure of attending the Participatory Innovation Conference (PINC) at the University of Southern Denmark on January 12, 2011. Dori Tunstall gave a remarkable closing keynote in which she performed a demonstration of three phases that design research/design anthropology/participatory design/user-centered design have evolved through in the past few decades. It was helpful to have her perspective on the key transitions:

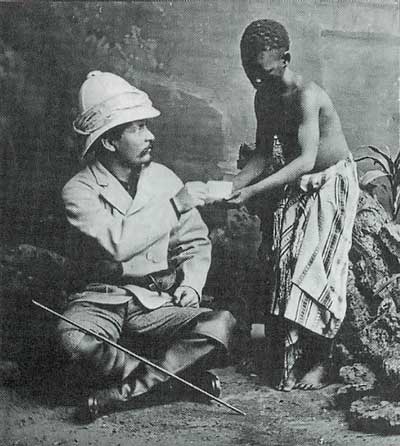

– In the beginning, design anthropology was about researchers as interpretive experts, delivering and recommendations to design teams and others.

– In the 1990s this evolved toward Participatory Design in which interdisciplinary teams participated in observations and defining insights. Insights are delivered in the form of experience models and personas. Researchers become facilitators with multiple, complex stakeholders involved.

– She proposes that the next phase of Design Anthropology will establish the academic foundation of this practice. With that will come a focus on social issues and an understanding of how objects affect the people around them. Designs are disruptions to the people in a culture and those disruptions should be studied. This study of objects and processes define what it means to be human. Design can seek to close the gap between the disruption and the ideal experience.

Dori is now establishing a program at Swinburn University in Melbourne, Australia. It seems to be a program that comes closest to the practice of Design Research as it has developed in the U.S., because of the focus on developing expertise and understanding around studying people and the objects and processes that they use.

From the website:

The purpose of the Master of Design (Design Anthropology) program is threefold:

She recommended some resources that help define this most recent stage of Design Anthropology, and her own work:

- Thinking of Things by Esther Pasztory (2005)

- Collective Joy by Barbara Ehrenreich (2007)

- Transmodernity by Rasa Maria Magda (2004)

- Linda Tuhivai Smith’s (1999) critique of how we conduct research in cultures

Many conferences have been conducted on this topic. Well, not directly (that would probably be more helpful). But Anthropologists do enjoy centering discourse around who should and should not be conducting research. I have since forgiven EPIC for the first Ethnography in Praxis Conference during which a near fist-fight that broke out over who “owns” ethnography. And EPIC has been much more welcoming toward design researchers since. But what EXACTLY are they defending? It’s very difficult to know what you don’t know. So us “outsiders” are often still in the dark. But the truth is, we can learn a great deal from the ethical and bias-lessening techniques of Anthropologists and Psychologists.

Many conferences have been conducted on this topic. Well, not directly (that would probably be more helpful). But Anthropologists do enjoy centering discourse around who should and should not be conducting research. I have since forgiven EPIC for the first Ethnography in Praxis Conference during which a near fist-fight that broke out over who “owns” ethnography. And EPIC has been much more welcoming toward design researchers since. But what EXACTLY are they defending? It’s very difficult to know what you don’t know. So us “outsiders” are often still in the dark. But the truth is, we can learn a great deal from the ethical and bias-lessening techniques of Anthropologists and Psychologists.

Many universities offer Psychology 101, and I think all Design students should take this, but few offer Anthropology 101. As a result, the fundamentals of Anthropolgy and Cultural studies have eluded me for the first 10 years of my career as a design researcher.

Last week, literally while in the middle of an ethnographic observation, I stumbled upon a book that helped tremendously. I was observing a college student, and during her two-hour homework session in the library, I needed something to occupy my attention, to remove some of it from the back of her head. I wandered over to the Education section (because it was fairly close) and found a book by Rebeka Nathan, “My Freshman Year: What a Professor Learned by Becoming a Student.” This book caught my attention because of the topic, but after reading her introduction, I flipped next to the back of the book, where the author reflects on the ethical dilemma of conducting research under cover. I learned from her discussion the careful ethical considerations that Anthropologists are taught that helped me to add integrity to my own research.

– Misrepresenting oneself to the culture being studied is inherently disrespectful. This was interesting to me, because often we do not want to reveal what the focus of our research is. So this discussion made me step back to make sure that I am not pretending or lying in my current research. I am not revealing the company that I work for to my participants, to help prevent bias, but I have been clear with them upfront why that is. In fact, my LinkedIn profile currently states that I work for “An Internet Company in Silicon Valley” and I point participants to that for credibility.

– Obtaining information under false pretenses. This sounds evil, but it can actually happen quite easily. For example, my participant had a Skype conversation with her best friend while I was observing her. I sat in the room, but was generally out of view of her friend. My participant did not point out my presence to the friend, and I wanted to observe a conversation as naturally as possible. But because that friend did not know that the conversation was being “recorded” (only note taking), I cannot ethically use the content of the conversation in my research. I will record the fact that it HAPPENED. But I won’t use quotes from it.

from Phsyics Web

“The Wisdom of Crowds” seems to be a sound idea, one many people get behind. But beyond the obvious application to user generated content, James Surowiecki runs into trouble trying to help businesses understand how to apply this principle in practice.

But I am enjoying hypothesizing that Roberto Verganti would agree that both he and Mr. Crowd are suggesting that good ideas (smart, accurate ideas in Surowiecki’s case, Design-Driven Innovation in Verganti’s case) comes from choosing the a diverse crowd and collaborating on ideas with them.

“The Wisdom of Crowds” describes the necessity of “cognitive diversity” to aggregate ideas, in fact, it is detrimental to continue to collaborate with a group of people who all think the same way about a problem. When you embrace the conflict that arises when a group of people with different perspectives hammer on a problem, better decisions result.

In “Crowds” the synthesis of ideas happens out in the open– the crowd does the work of finding the patterns and “truth” within the topic. In Verganti’s inspiration networks the synthesis may happen within the designer’s head as she or he aggregates multiple points of inspiration from diverse collaborators. But both emphasize the importance of reaching out beyond our own environments to find inspiration in new perspectives.

A strange article came out a bit ago, about how the engagement with Twitter is much lower than we believe. The strange thing is that they are basing it on the measured number of Responses and Retweets. Who knew that was the primary objective of Twitter? Not the designers of Brizzly or TweetDeck, two of the primary interfaces for “engaging” with Twitter.

A strange article came out a bit ago, about how the engagement with Twitter is much lower than we believe. The strange thing is that they are basing it on the measured number of Responses and Retweets. Who knew that was the primary objective of Twitter? Not the designers of Brizzly or TweetDeck, two of the primary interfaces for “engaging” with Twitter.

If ReTweeting is the way of showing engagement on Twitter (a big “if” because many of us just enjoy reading the Tweets) then the interfaces should be designed to encourage that. It would be simple to make ReTweeting more simple than any other interaction on the site/app. And I think that a few changes to the design could cause ReTweets to go up.

The fact is, Twitter is a very new way of communicating with people/friends/admirers/stalkers and people need some nudging toward how to make the most of it. Interfaces can do that, easily. But most of the services for Twitter focus on Tweeting and reading. So that’s what people do.

I do suspect that a primary reason that RT is a primary measure of engagement, is because it’s much easier to measure than time spent reading. Or level of enjoyment when interacting. The disappointing thing is that many programs do keep track of the tweets you’ve seen, so with some creative data analytics, they could tell us how much time people spend, and how many tweets are seen. Do you think TweetDeck has user researchers who will be presenting this kind of info at CHI? Hope so!

In the Carnegie Mellon Design program we were taught that Designers are experts in process, rather than topics. The pride of a CMU designer is that we can design “anything.” That works pretty well if you work in a consultancy, where everyone is expected to switch topics every few months, and enjoy it.

But when you work in-house, the expectations for your domain knowledge are much higher. I work for an internet company, and it is natural for people to expect me to know a great deal about technology. But I don’t. I know a great deal about people and how they behave and how they express themselves. And I know how to learn more about that. And I know how to get people to share their thoughts with me in a way that answers questions that are very difficult to answer.

But it erodes my credibility when I don’t know the latest TechCrunch opinion. So, of course, I try to read more blogs and articles. I try to use the latest apps and services. I have a twitter account: hillarydesres.

But in reality, I’m never going to spend all of my free time keeping up on the latest technology. But I’ve realized that through consistent collaboration with teammates, I learn far more than I would on my own. When I need to know the latest technology– or the latest anthropological theories– I know who to ask. I think of it as outsourcing my knowledge. I have all the knowledge I need– I just keep it stored in other people’s brains.