Category: Participatory Design

Helen Walters writes, once again, about how Design Thinking isn’t the magic bullet that some of us like to think it is, in a FastCo post. I found this paragraph helpful in articulating the value proposition of Participatory Innovation:

For designers to have strategic impact, they need to work with managers to ensure that the business elements of a project are being catered to, too. That might not play to the innate strengths of designers, but it’s vital for leaders to figure out ways for everyone to get along so that innovation can be a team sport. Otherwise, we’ll be left with bizarre stories such as the one that ran recently in The New York Times, with a Smart Design director arguing that the Flip camera was, in fact, just about perfect. Just not so perfect that Cisco didn’t decide to discontinue making the product. Executives don’t always make the right decisions, of course, and perhaps Cisco management did make the wrong call in this instance. But proclaiming that smartphones had no bearing on that discussion and arguing that all of the design decisions were correct smacks of hubris and myopia. Design doesn’t — shouldn’t — live in a bubble and designers need to bridge the divide between their world and business, not just lob ideas over the fence and hope for the best. As it stands, it takes a particular type of person who can span those two worlds. Those are the must-hire employees of the future.

Participatory Design acknowledges that we, as design researchers, are not seeking truth. What we gain from our interactions with participants is biased toward the questions we need to answer. The ideas that spark innovation and that are most inspiring to us as people who are intending to solve a problem—can come from many places.

With that in mind, Brendon Clark inspired me with the ways in which he has been exploring the boundaries of how much control he can give to others when he works with users and stakeholders in the field. Yesterday, in a chat with Brendon, a great influence of Participatory Design thinking for me, I realized myself how little control I give to those around me. He asked why.

“I… am trying to preserve the accuracy.”

Yet I have always acknowledged that the purpose of my approach is inspiration. When people ask me how I can stuffy only 6 people, I tell them that it only takes one clarifying story to change everything.

If I gave up some control to the designers and product managers in the field with me—to allow them to pursue the topics of the conversation that are most interesting—mightn’t we all be more inspired?

And the Participatory Design movement in Scandinavian, which I admire so much, has always been about bringing the user into the conversation as a equal participant. Easier heard than acted upon, apparently.

I see now how I tend to keep users in the dark during my field sessions—trying not to bias them by telling them what I want to know, or what I find most interesting. I remain neutral in the conversation– open and supportive– but still neutral, holding my card sort close to my chest, so to speak.

Brendon has been studying and writing about Performance as a way to put participants at the center of the conversation for innovation and design. He began his work, at the intersection of Anthropology and Participatory Design, with a focus on users and is now expanding his work to include stakeholders as participants as well. He says, “When you give people a stage, they naturally perform.” He sees our role as researchers as the people who create the stage.

So many product research projects focus on influencing a decision, for which the researcher provides very specific insights about a specific portion of the overall problem.The beauty of Participatory Design projects is that the focus in not only on the initial task-at-hand that needs to be solved by the group, but also that the unstated goal becomes raising the knowledge of the people in the room.

When engaging in formative, strategic research for my product teams, and by engaging them throughout the process, my goal is to inform my stakeholders about a broader, more holistic context of use.

I hadn’t thought about this particularly, until a design director at work said to my director, “I want to work with you. But my people can’t focus on anything but research that helps them design what they are working on right now.” [Read into that “can’t” what you will] His meaning was that I can’t spend time sharing insights with the designers that don’t directly answer questions about this widget or that widget. Very disappointing. Especially when I’ve developed good relationships with the Product Managers, Marketing Managers and Engineers by sharing stories and insights about user experiences that helps to raise there OVERALL understanding of how people use communication tools.

My purpose for this kind of sharing of insights is mainly driven by my belief that I am not at MOST of the meetings where decisions are made– if they are even made in meetings. I also can’t research every little question that comes up, “Should this button go here or here?” “Do people share photos or quotes more often?” Therefore I need to arm the decision makers with an empathy and understanding of how different users make choices, so that EVERY decision they make is a bit more informed by real end-users.

from Phsyics Web

“The Wisdom of Crowds” seems to be a sound idea, one many people get behind. But beyond the obvious application to user generated content, James Surowiecki runs into trouble trying to help businesses understand how to apply this principle in practice.

But I am enjoying hypothesizing that Roberto Verganti would agree that both he and Mr. Crowd are suggesting that good ideas (smart, accurate ideas in Surowiecki’s case, Design-Driven Innovation in Verganti’s case) comes from choosing the a diverse crowd and collaborating on ideas with them.

“The Wisdom of Crowds” describes the necessity of “cognitive diversity” to aggregate ideas, in fact, it is detrimental to continue to collaborate with a group of people who all think the same way about a problem. When you embrace the conflict that arises when a group of people with different perspectives hammer on a problem, better decisions result.

In “Crowds” the synthesis of ideas happens out in the open– the crowd does the work of finding the patterns and “truth” within the topic. In Verganti’s inspiration networks the synthesis may happen within the designer’s head as she or he aggregates multiple points of inspiration from diverse collaborators. But both emphasize the importance of reaching out beyond our own environments to find inspiration in new perspectives.

In the Carnegie Mellon Design program we were taught that Designers are experts in process, rather than topics. The pride of a CMU designer is that we can design “anything.” That works pretty well if you work in a consultancy, where everyone is expected to switch topics every few months, and enjoy it.

But when you work in-house, the expectations for your domain knowledge are much higher. I work for an internet company, and it is natural for people to expect me to know a great deal about technology. But I don’t. I know a great deal about people and how they behave and how they express themselves. And I know how to learn more about that. And I know how to get people to share their thoughts with me in a way that answers questions that are very difficult to answer.

But it erodes my credibility when I don’t know the latest TechCrunch opinion. So, of course, I try to read more blogs and articles. I try to use the latest apps and services. I have a twitter account: hillarydesres.

But in reality, I’m never going to spend all of my free time keeping up on the latest technology. But I’ve realized that through consistent collaboration with teammates, I learn far more than I would on my own. When I need to know the latest technology– or the latest anthropological theories– I know who to ask. I think of it as outsourcing my knowledge. I have all the knowledge I need– I just keep it stored in other people’s brains.

After working for several years at a design and innovation firm, I’d grown to rely on Designers for creative problem solving… sort of thinking of myself as the person who leads the framing of the interesting, relevant questions and Designers as the ones who lead the elegant solution-finding. But in my new position I’ve been without Designers on my team. But because I position myself as a Design Researcher, I wanted to deliver insights that had solutions, at least the beginning of solutions, attached to them.

That’s when I realized that this was a chance to rely on the kindness of teammates. And they’d probably enjoy it along the way. I turned each of my findings presentations into brainstorming sessions– presenting compelling user stories alongside opportunity areas. I asked questions like “Imagine that 10 years from now we are wildly successful as _______. What would that experience be like?” And asked engineers, product and marketing managers to grab a sharpie and some half-sheets of paper and tell me what I didn’t already know.

It has been a great way to understand what my brilliant teammates know about the opportunity areas– and they have diverse perspectives. It’s also been a great way to learn what is most surprising and inspiring to the teams. Some insights they nod their heads, sometimes they even say, “we’re already working on that.” But other insights spark great conversations, light bulbs pop up around the room. Those are the topics I dig deeper into.

The best part is that I did this before delivering my final report. So now, as I craft that massive presentation, I know what my stakeholders care about. I know more about it than I did before. And I have funny little sketches to illustrate many of the important points.

Insights must incite. If a fantastic insight falls in the forest and no one hears it, is it still valuable?

What Design brings to research to make it more suitable for innovation is not better research methods.

The creative-thinking and rule-breaking of design does little to improve the reliability of research… what it does bring is a new perspective on the problem:

- Seek more interesting users (extreme people with strong ideas and opinions)

- Ask more surprising questions (to learn the unexpected)

- Look between the lines (discover the latent needs that describe opportunity areas)

- Focus on the future (forget describing what is currently happen, predict what logically comes next)

- Focus on what is actionable (forget describing the entire experience, illuminate what has potential)

- Deliver findings in a compelling way (use visuals to make insights more accessible)

- Design the experience of receiving the insights (no more PowerPoint– get your listeners involved)

I have been practicing Design Research for nearly ten years now, in various contexts. And a recent conference hosted by DMI helped me take a critical look at how I can improve my practice.

Roger Martin has contributed foundational work to the conversation of what Design Thinking is and why it is valuable. From his definition I am able to see that Design contributes two distinctly different benefits to problem-solving:

1. A new way of looking at the problem

2. Creative tools for finding solutions

To me, this breaks down into two steps– though for many people these may happen instantaneously. When I think about my own current work, conducting user-centered research to help inform the future of Communications products, I realize that I haven’t been pushing hard enough on the second point. I enjoy the process of developing insights. Insights are compelling and exciting, and it’s rewarding to read between the lines and discover new opportunities. But to fully participate in Design Thinking, I need to deliver insights together with possible solutions.

In my current project, I am not partnered with a Designer to help me find creative solutions. I choose not to look at this as a barrier, but as an opportunity to engage others in my mission to find new solutions. I see now, after listening to a series of Design Thinkers at the “Re-Thinking Design” conference, that I need to turn my glossy presentation of exciting insights into a working session that engages different teams in helping me to shape the final part of my presentation– together we can propose solutions that make the insights more compelling and real.

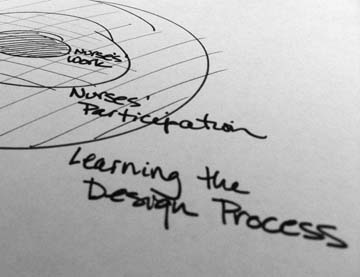

There is a complexity to systemic design challenges that is becoming clearer to me as we move through the hands-on phase of prototyping in context with nurses. The experience I am leading in this project has many experiences nested inside it. And it is useful to imagine how this project might be different if we realized the nestedness of these experiences in planning the phases.

Most of our energy, and the weight of the work, has been on “transforming” the 4 new hires within the client’s innovation group. This is a huge learning experience for them, and we wanted them to feel inspired and in-control of what they were learning, constructing the experience themselves. Which has, actually, made their experience rather self-centered–which is a wonderful way to be for people who are learning.

But the experience that is nested within their experience, is that of participatory design. The fundamental belief of the innovation group is that the ideas are developed by, with and for the end-user, in our case: the nurses. Which is a very un-self-centered approach. Egoless, even. And I think that we didn’t move into that mode of thinking soon enough. Now it is difficult for the team to give up their own needs for the needs of the nurses, and they continue to have the attitude of learners, without having the service mentality that comes with consulting and developing alongside the hospitals.

And to go one last step further, the ultimate experience that is nested within that participatory design process is that of the nurse in his or her daily work. The nurses are participating in designing something that will soon become a process that they need to follow as a requirement of their job. Thank goodness they have a chance to influence it and have their voices heard. But it needs to be more than a fun and engaging process. It requires them to think critically about what they can change and what they can sustain in their work.

So it seems that each of these experiences needs it’s own ground-rules and structure. And in thinking about a next project, it would interesting to try to identify all of them up front, and perhaps begin with the central experience as the starting point. Rather than working from the outside-in, as we have for this project.

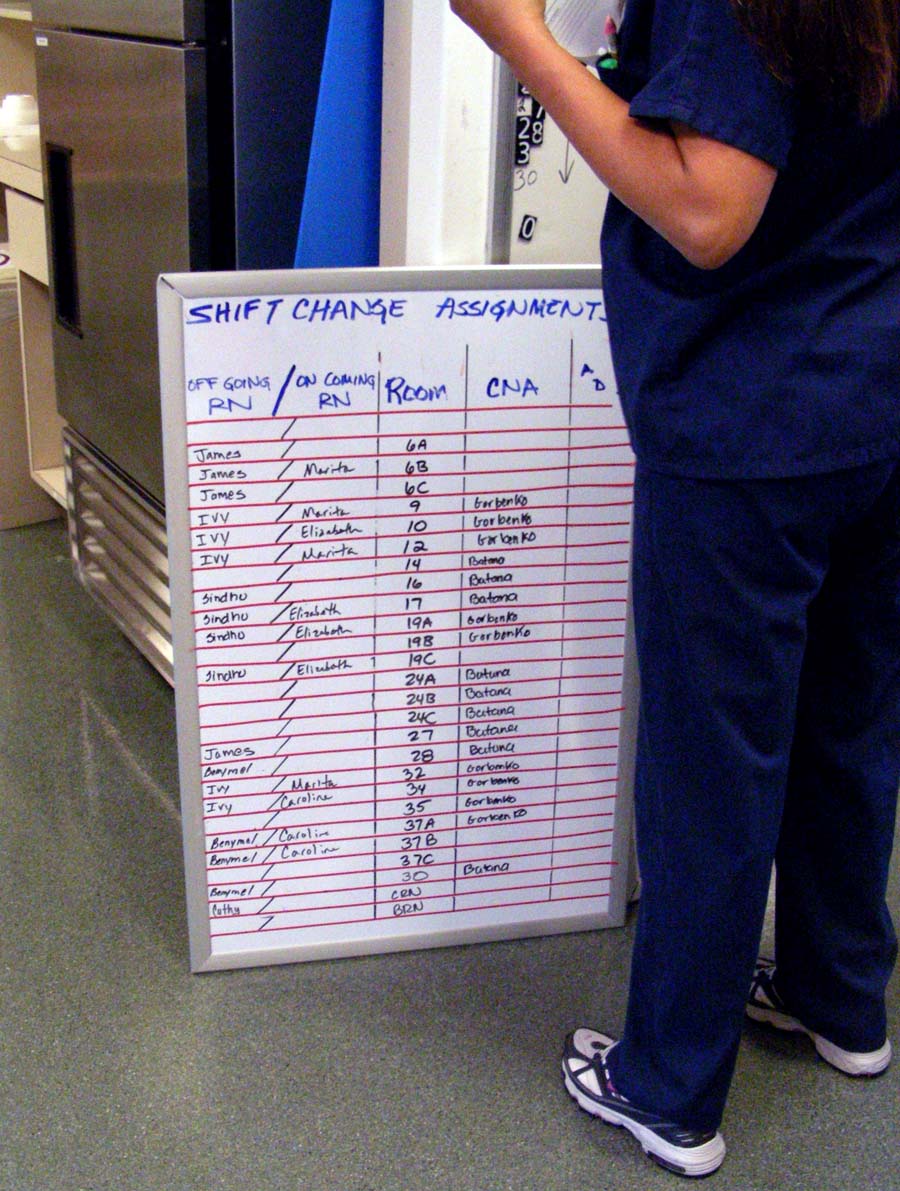

Our team has been talking about the steps of turning concepts into prototypes, and prototypes into tangible ideas. One interesting problem, and one insight arose from the discussions.

First, as a team, we can conflate the two important questions that we have about our concepts, and it can confuse and complicate our user research on the hospital floor. As we seek to understand whether the idea we are exploring is worth pursuing, we need to understand two distinct questions:

– Is this concept worthwhile?

– How would it work?

When we take a prototype onto the hospital floor and we don’t know whether we are trying to understand whether nurses are enthusiastic about the idea, or if it would really he helpful or how the idea could be implemented on the floor, we have trouble asking the important questions and understanding exactly what we are learning from our time on the floor.

So we are making extra effort to make sure that we separate out those two purposes. Testing whether the concept is worthwhile is a combination of both direct questions to nurses about how interested they are in the solution, as well as prototype tests that have observable outcomes, such as fewer patient requests or longer conversations between nurses and patients.

“How would it work?” is more of an investigation question. It takes a lot of legwork to understand the logistics of how a concept can be implemented on the floor… who answers the phones at shift change? How do nurses find the phone numbers they need, etc. But then it needs to be followed up with prototype tests that prove or disprove the methods for making it work.